At its best,

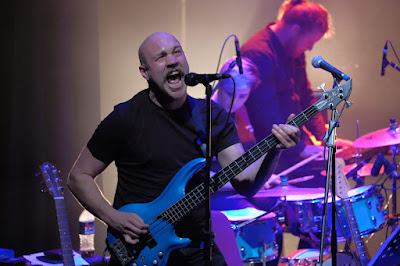

Bat Out of Hell: The Musical is very good. An unusual set is enhanced with great lighting and special effects, a very loud PA, and terrific individual and ensemble performances to recreate many of the

Meat Loaf hits you can belt out while driving up the motorway.

The plot is a bit bonkers. Elements of the Peter Pan story have been translated to a dystopian Manhattan where the Lost gang (stuck at age 18 due to frozen DNA) live in the subway tunnels while powerful tyrant Falco lords it over the city from his high-rise home. His daughter, Raven, turns 18, but despite Falco and his wife Sloane’s exciting story of how they became a couple, their daughter has been forbidden from leaving her home to spend time with the Lost, and in particular to ‘spend time’ with the motorbike-riding Strat.

The big set piece songs are beautifully performed. Live footage is relayed to a big advertising hoarding from Raven’s recessed upper room on one side of the stage. It’s not a perfect solution. Some of those at the very edge of the stalls or boxes can’t see the full screen, and it means that some of Raven’s songs are sung to camera rather than out towards the audience. But it does allow some detailed close-ups of props that bring personal touches to the narrative.

The direction (Jay Scheib) and choreography (Xena Gusthart) at the start of Raven’s birthday party are like something out of Calixto Bieito’s Turandot opera (performed by NI Opera on the same stage just over seven years ago). Stark choices for outfits and wigs, very sharp blocking, and beautiful detailing in the choreography.

Paradise by the Dashboard Light is a dazzling combination of props, costume and performance with real life couple Rob Fowler and Sharon Sexton (just back on tour after maternity leave) going the extra mile to make Falco and Sloane’s sultry flashback sequence sizzle. It’s also one of the moments that delivers the most physical humour and the first of several epic explosions. (Though the knowing use of comedy with more than a nod through the fourth wall to the audience – reminiscent of

The Rocky Horror Show – is quite inconsistently applied throughout the show.)

The first act concludes with a sense of tragedy. Glitter cannons, flames and choreography are thrown at the titular song Bat Out of Hell. As the music ends, the cast are made to disappear as the red light focuses on the body of Strat. It’s one of several really well-crafted moments. (And it brings Henry the hoover and a large backstage team out onto the set to clean up for most of the duration of the interval.)

Martha Kirby (playing Raven) sings a mesmerising version of Heaven Can Wait at the opening of Act Two. Look out for Sharon Sexton’s entertaining “Mum dancing” when Sloane leaves Falco Towers to and joins the Lost gang during You Took the Words Right Out of My Mouth. There’s real narrative pressure to reunite Sloane with her abusive husband. (Spoiler alert: estranged couple gets back together, shock!) Falco successfully asks for forgiveness on the second of two attempts, yet there’s no sign of contrition, proper remorse, or consequences for his violent actions. Hmmmmm.

While Joelle Moses and James Chisholm’s characters Zahara (one of the Lost who works for Falco as a nurse) and Jagwire (her suitor) don’t get much time to develop their personas, their commanding voices are behind some of the show’s top musical moments (

Two Out of Three Ain’t Bad and

Dead Ringer for Love).

The grand finale ten-minute rendition of I’d Do Anything For Love (But I Won’t Do That) neatly bounces lyrics between the main characters to round off their stories. Throughout the two-and-a-half-hour show, Glenn Adamson flexes his pecs, leaps around the stage like a beefcake Tigger who has eaten too much honey, and sings ballad after ballad as Strat. It’s a feat of stamina and endurance as well as memorable theatre.

The highlights are tempered by a few moments when the show’s energy is allowed to drain into the subway sewer. Transitions between some scenes have awkward musical junctions. Jim Steinman’s music and lyrics are so much better than his dialogue. While the backing vocals from the ensemble can lift the most recognisable numbers up onto a different level, their impact is weaker in more mundane moments. And then there’s the quintessential Meat Loaf motorbike that regularly revs onto the stage before somewhat awkwardly and unnaturally reversing off stage like a mobility scooter that’s lost its reversing beep.

It’s the loudest touring musical theatre show I can remember. Very well mixed, but writing this review an hour after the show ended, my ears are still ringing. If the mark of a good show is that you’d happily return to see it again, Bat Out of Hell: The Musical is a winner. Catch it if you can before it finishes its run in the Grand Opera House on Saturday 27 August and then transfers to Dublin for a two week run.

Photo credit: Chris Davis

Enjoyed this review? Why click on the Buy Me a Tea button!

%20and%20Rosie%20Barry%20(Ethel%20Gillingham)%20in%20Carson%20and%20the%20Lady.jpg)

%20James%20Doran%20(Lord%20Carson),%20Rosie%20McClelland%20(Lady%20Massereene)%20and%20Conor%20O'Donnell%20(Ballentine)%20in%20Carson%20and%20the%20Lady.jpg)

%20in%20Carson%20and%20the%20Lady.jpg)

%20in%20Carson%20and%20the%20Lady.jpg)

%20&%20the%20cast%20of%20Blood%20Brothers-%20Blood%20Brothers%20UK%202022%20Tour-%20Photo%20by%20Jack%20Merriman.jpg)

%20&%20Nick%20Wilkes%20(Policeman%20&%20Teacher)%20-Blood%20Brothers%20UK%202022%20Tour-%20Photo%20by%20Jack%20Merriman.jpg)

.jpg)