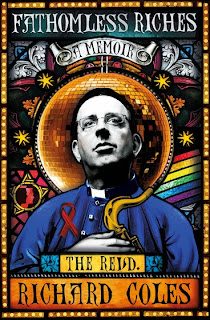

Now a parish priest and radio presenter, Coles documents his upbringing and gravely disappointing O-level results at a fee-paying school before transferring to drama school and finding a growing confidence in his sexual identity as well as his first steps in a lasting relationship with drugs.

His musical talent with saxophone and keyboards led to his involvement with band Bronski Beat before forming The Communards with Jimmy Sommerville in 1984, achieving chart success with Don’t Leave Me This Way, touring, partying, arguing and beginning the long slide towards the band’s split in 1988.

While not conscious of it at the time, Coles was often surfing the cultural zeitgeist and throughout the book there are references to familiar events and people. The film Pride and play Pits and Perverts reminded 2014 audiences about the Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners movement formed during the Miners’ Strike which left a lasting legacy within the TUC and Labour Party of treating lesbian and gay rights as equality issues. Bronski Beat played a benefit concert for LGSM. Later in the book there’s a photo of Coles staying over at Hillsborough Castle as the guest of Secretary of State Mo Mowlan. A few years later he conducted her funeral.

Amongst the music and partying, about a third of the way through the book a terrible sadness descends as Auntie Ada came to visit and AIDS killed many of Coles friends and acquaintances. The sense of loss, and hopelessness is overwhelming. Chapter after chapter, close friends are infected with HIV and die.

This was to be a common experience over the next few years, meeting in a dead man’s flat for the distribution of their effects, or the concealment of things which needed to be concealed from their families, and sometimes, most awkwardly, negotiating funeral arrangements with a middle–aged couple who had only just learned that their son was gay in time for him to die.

The Communards’ success with their first album was not easily replicated and Coles admits to being jealous that “Jimmy got more attention than me, more credit than me”. Despite staying in larger and larger hotel suites and travelling with an expansive entourage, Coles “sulked about being ignored in interviews” and “hated it that when I was signing an autograph the fan would see [Jimmy Sommerville] and pull their book from my hands leaving a zigzag of biro where my name should be”. Sickness caused Coles to worry about his own health.

… I got a message to call the doctor. ‘Good news,’ he said, ‘I have your test results. They came back negative.’ And that is how I became the only person ever to be disappointed to hear he was not HIV positive.

Having jumped the gun and told colleagues and friends that he was HIV positive, Coles lived with the lie. “I was treated more considerately than I had been and it did mean I now had a leading role in the drama.” Years later he swallowed his pride and made humiliating confessions.

Drug abuse and his ability to fund it took over Coles’ life, while presenting on Radio 3 and some musical commissions kept him in work.

Choral Evensong in Edinburgh and a visit to York Minster (in which he “went in a tourist but came out a participant”) reignited his childhood Anglican experiences and led to a serious flirtation with becoming a monk and a wobbly walk along the Anglo-Catholic tightrope in which he signed up for a theology degree from Kings College London, crossed over to Catholicism, before returning to train for ordained ministry at the Anglican College of the Resurrection at Mirfield in West Yorkshire.

Coles reserves his harshest judgements for himself. While many friends and co-conspirators are named throughout the book, some blushes are spared with enough anonymity granted to shield identities. His honesty and frankness extends to his feelings for the college at Mirfield, calling out the bullying from the year above and his disappointment at the behaviour he and other students experienced.

I don't think I really believed in evil until I went to Mirfield.

Ouch! While his entry into ministry has been unconventional, the emotions, experiences and talents that he brings to his calling are clearly usable by the church.

Romantically, Coles suffered from sustained sadness with his interest and lustful notions not being consistently returned by many of the people he longed for. That frustration extends to institutions as well as people.

I love the BBC. I love the Church of England. But it is not wise to love organisations because they do not love you back. They do what organisations do, sometimes close ranks, lie, betray, disappoint, take you out at dawn and shoot you. All institutions are demonic, a cleric once observed, but the ones that have the clearest sense of their own high calling are most vulnerable to demonic activity. I support it is because where aspirations are high and reach is limited there’s plenty of room of disappointment and frustration to play out and that can curdle one’s feelings for a place.

Coles enjoys the fine things of life. His stint in The Communards has left him with a ‘pension’ that allows him to book into the best hotels, enjoy fine food, wine and clothes. While he has the capacity to appreciate what he can afford, and while he’s happy in the company of those who don’t share his tastes, some of the later anecdotes in the book left this reader with the hope that he discovers freedom in reining in some of these excesses and rediscovers a little of his monastic leanings.

Fathomless Riches was a great Christmas present. Its author’s honesty and ability to shock and sadden makes it an engrossing read. Throughout the darkness there is thread of hope; hope imbued with faith that ultimately ends with Coles’ sense of peace in his new vocation.

Ultimately I hope that Coles will write a follow-up memoir, starting off with settling into parish life of Finedon in Northamptonshire and carrying on to document his journey through ministry, civil partnership and beyond. While he knows “second albums are notoriously difficult”, his capacity to tell a story deserves another outing.

No comments:

Post a Comment