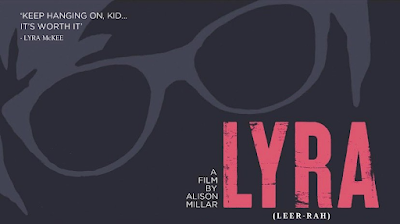

Alison Millar’s film about her friend Lyra is an astonishing reminder of the young woman so many of us loved. A friend who hundreds, probably thousands, of us felt we should go out of our way to encourage when we’d meet.

Family camcorder footage takes us back to Lyra as an infant, always bespectacled, always playful. It’s painful to hear her voice again, with extracts from clips from mobiles of friends and family, and snippets of conversation from dictaphone-recorded interviews. It’s a joy to remember her dress sense, her coordination, her unbounding love for her young niece, and the way Marie the cat invaded her personal space at every available opportunity.

Fragments from Lyra’s writing are typed onto the cinema screen. Lyra wasn’t a fast writer: footage in the film includes her describing the “crippling” anxiety she felt when sitting down to write. She never wrote a long sentence when two shorter ones would have more effect. Journalistic in style, yet with sublime adjectives. There’s an unbearable irony that her investigations into unsolved disappearances and murders are now followed by a search for justice in her own killing.

On her return from a trip to the US, Lyra presented at the TedxStormontWomen event. The film includes a chunk of that talk as Lyra wrestled with her experience as a gay woman who faced disapproval and condemnation from organised religion in Northern Ireland (though in conversation she’d point out individuals who didn’t fit those stereotypes and characteristically ask why they were the exception) and the much more accepting attitudes she stumbled upon when the press junket visited groups and found out about their work in the aftermath of the shooting that killed 49 people in a gay nightclub in Orlando.

I’d put Lyra’s name forward for the trip. She’d only recently learned to drive, so we met up afterwards in Belfast Castle, somewhere she reckoned would be easy to park. I still wear a Kennedy Space Station pin on my coat that she brought back from the group’s visit to NASA. That sequence in the film is a lovely reminder of how those weeks away had broadened her understanding of the complexity of so many subjects, yet an excruciating reminder that the bundle of joy who described herself as “the most annoyingly curious person you’ll know” can never be bumped into on the street or at an event.

If Lyra is a celebration of a life cut short, it’s also a testament to a family – particularly through the actions of her mum Joan and big sister Nichola – who believed that wee Lyra should not be constrained by circumstance, post code or background. While Lyra might have been seen by others as an underdog, she found herself empowered to empathise with others and help tell their stories.

The grief of her family and her partner Sara is agonising is watch and listen to. The arc of the 92-minute film touches gently on the way that victims can lose their identity and become part of the latest chapter in a conflict/post-conflict/peace process narrative, spoken of by politicians rather than represented by families. The commentary on the political stasis at the time of Lyra’s death and funeral is so apposite to today’s stalemate at Stormont.

David Holmes’ unobtrusive soundtrack tenderly underscores the mood of the on-screen journalling of Lyra’s life. While a lot of the footage was captured by documentary maker Millar, Mark McCauley’s additional cinematography is outstanding with a rich use of light and taking full advantage of the widescreen format for the visuals across Belfast and Derry.

One advantage of previewing films in a near-empty cinema is that I can gurn my lamps out without too many people realising. But if you’re more game than me, you can watch Lyra in the Queen’s Film Theatre and other cinemas from Friday 4 November.

1 comment:

Lyra was exceptional and a joy to know

Post a Comment