The Spiegeltent was one of this year’s Belfast Festival gimmicks. It’s a German construction that tours around the world, hosting its own cabaret shows, and offering a venue for performance, musical and spoken word events. It’s a quaint venue, laid out with circular tables and chairs on the main floor, and bench seating around the edges.

The Spiegeltent was one of this year’s Belfast Festival gimmicks. It’s a German construction that tours around the world, hosting its own cabaret shows, and offering a venue for performance, musical and spoken word events. It’s a quaint venue, laid out with circular tables and chairs on the main floor, and bench seating around the edges.

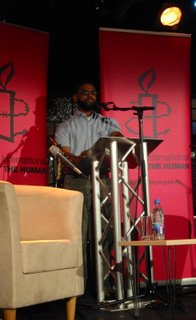

On Saturday night it was packed as the tent hosted Moazzam Begg’s Amnesty Lecture. Patrick Corrigan, Northern Ireland director of Amnesty International kicked off the show.

Born in Birmingham (UK, not Alabama) Moazzam grew up in the UK. I’d think it’s unfair to suggest that his story also shows him to be a political activist. Willing to be involved, and get his hands dirty understanding and the working in some of the world’s trouble spots. Nine visits to Bosnia under his belt before heading out to start a girls school in Afghanistan (where female education wasn’t popular under the Taliban).

During the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, Moazzam and his family moved to Islamabad in neighbouring Pakistan for safety. It was there that the Pakistani Security Police picked him up and shipped him back to Baghram Airbase. A year later he was moved to the US facility at Guantanamo Bay. On 25 January 2005, after a prolonged and high profile campaign by his father that was causing increasing political embarrassment to the UK government, Moazzam was released along with three other UK citizens, without any charge, apology or compensation.

During the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, Moazzam and his family moved to Islamabad in neighbouring Pakistan for safety. It was there that the Pakistani Security Police picked him up and shipped him back to Baghram Airbase. A year later he was moved to the US facility at Guantanamo Bay. On 25 January 2005, after a prolonged and high profile campaign by his father that was causing increasing political embarrassment to the UK government, Moazzam was released along with three other UK citizens, without any charge, apology or compensation.George W Bush* described the Guantanamo inmates as amongst the most dangerous men in the world. Sitting at the front of the Spiegeltent about three metres away from Moazzam Begg, I didn’t feel at all uncomfortable. He’s a highly articulate and quick witted man, with a gentle spirit that belies his incarceration. A perfect speaker for the festival. He’s also surprisingly short - at least a foot smaller than the actor that played him in the Guantanamo** play in London’s West End!

* I’m writing this up on the BA flight across to San Francisco! (I bet I’d get a long grilling at customs if they knew the kind of festival event I attend.) But the BBC World News briefing that’s just been shown suggests that Bush hasn’t had such a good night at the US elections.

** Walking past the theatre on the search for somewhere to eat I caught one of the final performances of Guantanamo in London’s West End. It was a disturbing play. it told the story of real people, including Moazzam, who were detained in Cuba at that time. As the final lines were delivered and the house lights went up, the orange-suited prisioners (actors) stayed in their caged cells on-stage, continuing to do their exercises, to say their prayers. The audience left in complete silence, only broken by chinks of change being dropped into collection buckets (for Amnesty or a legal fund, I can’t remember).Moazzam observed that although the world is focussed on Guantanamo as the most notorious prison (beating even Alcatraz?), it’s not the worst. Overseas detention centres in Egypt and Morocco, where non-US operatives interrogate using local customs and practices on behalf of the US are a lot more sinister.

“Ignorance breeds violence. We should seek knowledge.”

“Is torture ever justified? No. Why any debate?”

“Coming to Northern Ireland, of all the audiences I’ve spoken to, I thought this would be the one I learnt the most from, rather than just giving. Northern Ireland knows about oppression, internment, kangaroo courts. What am I going to tell them that is new?”He spoke about the dehumanisation of both the detainees and detainers. It was too easy he suggested to turn prison officers into figures of hate. Whether through instinct or premeditation, Moazzam became friendly with some of the guards at Baghram and Guantanamo. A tenet of the Islamic faith states “do not allow your hatred of people to do them an injustice”: helping him not to demonise all US soldiers. (He was later approached to give a character witness for one guard that was being court marshalled (and convicted) for prisoner abuse.)

“The war on terror isn’t about justice. It’s about payback. It’s about revenge.”He spoke very little about the exact circumstances leading up to his arrest and detention, nor said much about his treatment in Baghram or Guantanamo. Twenty minutes into his lecture, Moazaam’s generous spirit and lack of bitterness is amazing. He so doesn’t play the victim card.

He also resisted any attempt (including my opening question) to make any judgement or comment on how the UK government had helped or hindered his release. Though he was appreciative of the MI5 officers who interviewed him in 2003 and left him a copy of Jeremy Paxman’s The English: A Portrait of a People

William Crawley hosted the question and answer session after the lecture. While waiting for the restrained audience to bubble up with some questions, he probed Moazzam about some of the allegations made against him: owning night-vision goggles (a single eye night sight used by aid groups in Bosnia to see in the dark) and militant Islamic literature (a copy of the Koran). And his previous conviction for benefit fraud (years ago) isn’t relevant to the discussion.

I’ve a moral problem. If I take the position that people are innocent until proven guilty, then Moazzam is a political activist who has had no charges placed against him, and was wrongly incarcerated in terrible conditions against his human rights. I’d shake his hand and wish him all the best as he works with families who have loved ones (mostly fathers) locked up at Bush’s behest around the world, and promotes his book Enemy Combatant: A British Muslim's Journey to Guantanamo and Back.

But if I’m honest there’s another thought that crosses my mind. And I’m nearly too ashamed to admit it. But Moazzam survived detention. He knew to befriend the guards. What if there is something in the (mis)information being spread by the US about him to this day, leaking stories to the US press. As a free man, has he fooled his Amnesty hosts? Is his gentle spirit a cloak for a more sinister desire to undermine the West and the War on Terror?

I have to choose. And I have to choose not to merely give him the benefit of the doubt, but to accept the facts as they stand. Moazzam hasn’t been formally accused of anything that can stick to keep him locked up. On return to the UK, he hasn’t been put under house arrest and monitored around the clock by beefy armed guards. He lives with daily rumour and innuendo, but avoids engaging with it. He talks sense. I want to read his book. And I’m glad he’s a free man. I don’t think it’s safe to think otherwise.

1 comment:

Thanks for sharing this.

Just seeing him speak, you can tell he is not capable of that which they accused him of and even the authorities saw that which is highlighted by the fact that he (as you said) was neither charged nor put under control orders.

Post a Comment