Dan Gordon’s play The Boat Factory staged its world première at the “Shipyard Church” in East Belfast yesterday. It’s the church with a purple neon cross lit up on its tower at the bottom of the Lower Newtownards Road. Celebrating the 130th anniversary of its opening later this month, the church would have been filled in its early years with families working at or connected with the shipyard.

Sometimes sitting there on a Sunday morning I wonder what the emotion must have been like the Sunday morning after they’d heard about the loss of the Titanic. A ship that hundreds of the congregation would have spent years working on. Gone. Wiped out on its maiden voyage across the Atlantic.

Last night’s staging of The Boat Factory certainly won’t be sinking without trace. It’s part play, part documentary, plotting out the development of the shipyard in Belfast, as well as charting the social history of the shipyard workers. To be honest, it filled in a lot of gaps in my knowledge of the area and the history of Harland and Wolff.

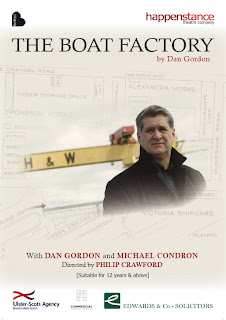

Produced by Happenstance Theatre Company and directed by Philip Crawford, the play is a two hander, with Dan Gordon playing Davy Gordon (based on Dan’s father) and Michael Condron cast in the role of Geordie Kilpatrick as well as filling in for countless other minor characters throughout the show. (There’s even a quick Paisley impression for good measure.) I caught up with Dan Gordon afterwards – watch the video.

“Too many bends, not enough depth,

can’t get the big boats in;

that river, that Lagan, that Lough

that Belfast.”

With a history of commerce around Belfast Lough for hundreds of years, it took men with vision to scoop up the sludge and create Queen’s Island, bringing the land out to meet the deep water to allow Harland and Wolff to build their ship-building business.

Davy grew up in a house where all the boys ended up working in the “boat factory”. Getting in the door was only the beginning of his adventure. Starting out as an apprentice joiner and carpenter, the audience listens to Davy as he remembers suffering the initiation pranks and learning to celebrate the traditions of the yard.

There is an abundance of dialogue: memories, conversations and at times lists of people and tools that turns into poetry. The dialogue is littered with portions from training manuals and instructions given to the apprentices, who spent the first few years learning about the tools and the practices of their trade.

“Both hands should always be behind the cutting edge.”

Apprentices also spent time learning the layout of the vast site, as well as the vocabulary, the names and the nicknames. The play had plenty of humour, innuendo and fart jokes, as well as pathos and an ending that had many in the audience reaching for a hanky.

The set is simple. Scaffolding towers, black crates, and a backdrop showing an old map of the area around the ship yard.

Geordie’s an eejit. He spends his lunchtime climbing high up in the yard (cue, climbing the scaffolding!) to look out over the yard and across Belfast. Yet there’s hidden depth behind his jokey persona. A fascination with literature, and in particular Moby Dick. The yard was full of “philosophers and parsons” and amazing characters around every corner.

But it wasn’t all clean fun. There was bullying. And it supported a variety of scams ranging from small homers making Christmas presents and toys for the family to a complete fitted kitchen business serving East Belfast with the knowledge and participation of the foreman. Following Ishmael’s example from his favourite novel, Geordie made himself a coffin!

The play dealt with the Titanic, but avoided taking the sentimental approach.

“If she hadn’t sank, she’d be long forgotten by now. Just another number and scrap. Look at the Olympic, built at the same time and scrapped after 26 years in the Jarrow boat yard. We’re working on ship number 1384 the Juan Peron. Near one thousand ships have been built since boat 401. We didn’t just build the Titanic you know.”

In the days before risk assessments and the Health and Safety Executive, scaffolding was there to get the workers high enough to do their job, but keeping safe was their own lookout.

“The accidents showed you what was wrong – that was the way.”

While jumbo jets ended the luxury liner business, asbestosis prematurely ended the lives of many workers in the boat factory.

Like a theatre company from the 1950s, Happenstance are touring around unusual venues – mostly avoiding proper theatres – and taking the play into the heart of various communities: halls, schools, even a prison. Old fashioned community theatre.

The play strongly connected with the East Belfast audience last night, and seemed to validate many of the legends and perceptions they had inherited as they grew up in the shadow of Samson and Goliath.

If you get a chance, I would recommend that you catch a performance of The Boat Factory as it tours around Northern Ireland over the next two weeks.